The overlooked currency of trust.

We are more motivated when we work together.

I believe this to be the missing ingredient in economic game theory. It is a factor often ignored by economists as ‘Irrational’.

Yet everything irrational seems to be motivational.

The Disjunction Effect.

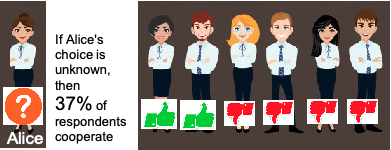

Researchers, Shafir and Tversky found that test subjects played the Prisoners’ Dilemma game differently is the actions of Alice is already known to Bob before Bob makes his choice.

When Alice’s decision was NOT known to the respondents, then 37% of them opted to cooperate. Roughly 2 in 6, including Bob.

But when Alice’s action had already been revealed, Bob dropped out. Now we’re down to just 1 in 6 supporting Alice’s good action.

What the hell, Bob?

Shafir and Tversky thought this to be ‘quasi-magical thinking’ surmising that Bob thought he could somehow influence the actions of Alice, but not if they are known already.

Authors Dixit and Nalebuff have called this theory ‘completely illogical’, and I agree because I believe it isn’t true.

I believe that the end-goal of much of these choices, indeed most of our decisions, isn’t about money as much as it is about the currency of trust.

Buying trust

How inclined would you be to go bungee jumping with some friends?

Compare that to going alone.

You end up doing the same thing, which is really just falling off a bridge, but it counts for SOMETHING when you do it with friends, and not nearly as much when you do it alone.

That extra value is trust.

The more of a bond you have with a person, the more you know that they are there when you need them, the more you can call on each other to do a potentially unpleasant activity together, the more trust – in oxytocin form – is paid out when you do.

We crave this kind of experience, and will go to great lengths to feel that trust in our daily lives.

Bob needs love

So back to the experiment. What’s missing? What is Bob looking for?

Last week I wrote that a game of trust is made up of three parts: agreement, uncertainty, and opportunity. If one is missing, there is no trust.

In this experiment, uncertainty is missing, so there is no risk, so no trust to be gained with either of Bob’s options.

No trust available? May as well choose the most profitable.

Bob’s love-starved Ventral Striatum

The other change was that as soon as uncertainty was removed, the pot of money went from the abstract to the real very quickly. No longer is it a possible pot, dependent upon the unknown actions of another, but a real pot which is too big a temptation for five out of six of us, it seems.

For Bob, and the rest of us, we’ve got stuff to buy with that money, for ourselves, for our partners, for people close to us. Bob could buy a beer for his army buddy with that money. Or tickets to an awful film.

How can we use this?

With any activity, ask the three questions mentioned to see if it is a game of trust:

Is there agreement?

Is there uncertainty?

Is there opportunity to act?

Make a set of rules that all can agree on, including personal responsibility if those rules are broken, and slowly extend trust for higher and higher stakes until such a bond is formed that it feels better to act as is mutually beneficial than to not.

Tim Ferriss advises in his book The Four Hour Work Week that people work best when given some trust and autonomy, so instructs anyone who he has delegated work to that they can make decisions for amounts up to $200 without even asking him, which freed up most of his time.

Ferriss may have intended merely finding new ways to slack, but he found that the effect on their happiness, teamwork, quality of work and extra discretionary effort was extraordinary! He got to be lazy AND a great leader!

So, find small ways to trust, with its agreements, authority and uncertainty, and you will eventually find you can trust them with full projects, and they will love you for it.